Pulling power

They have stood in lowly cattlesheds, they have shaped our agricultural history, and today they still help to cultivate half of the world’s crops, but what exactly IS an ox? I asked the question for Country Life magazine. They published it on January 15 2025 with some splendid images.

We are familiar with the term ox – those lowing beasts attending the Nativity, the ox-eyed daisy – and we know we can have the constitution of one, but can we define such an animal? What exactly is an ox? All cattle can potentially be oxen and all oxen are cattle. The ox is simply a bovine that has been put to work. Nearly every breed of domesticated cattle (Bos taurus) is capable of being a draught animal, but it was usually the docile, castrated males from the larger breeds who were used, while the cows were kept for milk.

Oxen have been hard at work in this country since their pulling power was exploited by Neolithic people struggling to haul out tree roots and clear land for farming. Over in Mesopotamia, Queen Puabi was riding around in a gold and lapis lazuli-decorated oxen-drawn wooden sled – the earliest surviving vehicle. All through the introduction of the wheel during the Bronze Age, and the metal-tipped Iron Age scratch plough, oxen stayed fully employed – and remained so for many hundreds of years.

They worked on farms both large and small, pulling ploughs and carts. On the roads, oxen were the original heavy goods vehicles, taking loads of logs and stone around the country. Their ability to pull a static load from a standing start was unsurpassed, making them truly the best way to overcome inertia. Steady, strong and reliable, they went at a ploughman’s walking pace and left their mark on the language. An acre is the amount of land that could be ploughed by a team of oxen in one day, and its length, a furlong (220 yards), is the distance they could manage before needing to rest. An oxbow is a piece of wood that curves below the neck and joins the yoke, the shaped hardwood bar fitted in front of the shoulders of each pair.

Oxen were matched with others equal in size and were also named in pairs, as the late Michael Williams recalled when writing in Farmers Weekly ten years ago:

‘Once a pair was selected, they became each other’s companions for life, working side-by-side and never far apart, whether grazing in meadows or sleeping in the ox barn. Each ox had a name, and within the pair one had a single syllable name, and one had a longer name. So Quick and Nimble, Pert and Lively, Hawk and Pheasant, all spent their working lives together.’

The beasts would also have been close companions of the farmer, often occupying the lower or adjacent part of the farmhouse, all getting up together in the early light to get to work.

The working ox was frequently shod, with each part of its cloven hooves clad with iron. Less able – or amenable – to stand and offer each hoof in turn like a horse, an ox needed to be roped, tipped over and held down for the farrier to do his work. Small segment-shaped ox shoes can still turn up on ploughed fields, along with brass ox-knobs, created to protect both handlers and fellow oxen from the sharp horn tips.

Until the end of the eighteenth century, the ox continued to pull ahead of the horse as the most commonly used draught animal. The ‘plowman who homeward plods his weary way’ in Thomas Gray’s 1751 Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard would likely have been following a team of bovines, perhaps taken from the lowing herd that ‘wind slowly o’er the lea.’

The ox’s strength was always superior to native breeds of pony. Heavy horses were initially only bred and reserved for the military, but gradually more draught horses from the continent began to be introduced. Although faster, these high-performance vehicles required expensive fuel in the form of grain, whereas the low-gear ox could survive on rough grazing and straw. Oxen could pull heavier loads, and their cleft hooves had better grip. They could be home-bred on the farm, and, most economical of all, could be fattened and eaten at the end of their working life.

Another agricultural reformer, Henry Home, Lord Kames, championed the ox in his 1776 The Gentleman Farmer, declaringthat ‘there is not any other improvement that equals the using of oxen instead of horses’ and going on to explain that not only were horses much more costly to buy and to shoe, they were prone to far more diseases and lameness, and required grooming. Even their dung was poorer quality, he asserted, and gave several instances of oxen-driving farmers who managed just as much ploughing as their horse-powered neighbours.

Nevertheless, the draught horse began to nose ahead as the impetus grew for speedier, more efficient farming in increasingly enclosed fields. While oxen were suited to the medieval open-field system, plough horses were nimbler at turning, ensuring every corner of the new, smaller fields could be cultivated. The ox’s place on the roads was then undermined by the coming of the railways in the mid-1800s, while a growing demand for meat from the booming cities was matched by the selective breeding of cattle for the table rather than the plough.

By the 1850s, the working ox was becoming a rare sight in the northern half of the country, although it was still preferred for a few decades on the limestone and chalk uplands of the south-west. Largely vanishing before photography became widespread, there is little visual documentary evidence of the bovine contribution to British agriculture.

The ox is celebrated in art as one of the humble creatures with a walk-on part in the Nativity. It can be seen in works by Filippino Lippi (Adoration of the Magi, 1496), Jacopo Bassano (Adoration of the Shepherds, 1546) and Albrecht Dürer (Adoration of the Magi,1504). In Thomas Hardy’s poem Oxen, published on 24 December 1915, a group of old men sitting by the glowing embers of a hearth remember the story from their childhood that oxen continue to pay homage on that night: ‘If someone said on Christmas Eve, ‘Come; see the oxen kneel/…I should go with him in the gloom/Hoping it might be so.’ The poem, with its longing for the dependability of the past and its fragile hope for the future, was written at a desperate point of the Great War and has been set to music many times, including by Benjamin Britten, Gerald Finzi and Ralph Vaughan Williams.

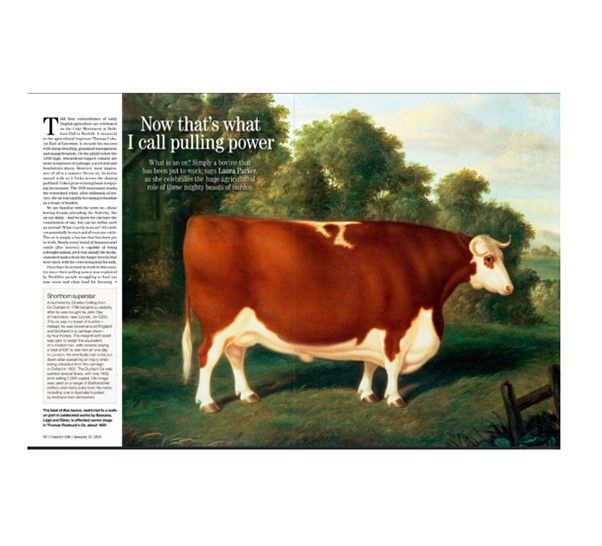

Shorthorn superstar

A bull bred by Charles Colling from County Durham in 1796 became a celebrity after he was bought by John Day of Harmston, near Lincoln, for £250. This ox was no beast of burden – instead he was toured around England and Scotland in a carriage drawn by four horses. The magnificent beast was said to weigh the equivalent of a modern tonne, with crowds paying a total of £97 to see him on one day in London. He eventually had to be put down after an injury while getting out of the carriage in Oxford in 1807. The Durham Ox was painted several times, with one 1802 print selling 2,000 copies. His image was used on a range of Staffordshire pottery, and many pubs bore his name, including one in Australia founded by brothers from Derbyshire.

On the Ox-trail

Oxford, originally Oxnaforda in Anglo-Saxon, was named for the place that cattle (herded as well as yoked) could safety ford the River Thames where it branches into several smaller channels. Around the country, settlements such as Oxenhall, Oxton, and Oxgangs in Edinburgh are all oxen-related places. (An ox gang is the land which could be ploughed by one ox in a single season.) Oxted in Surrey, however, has another derivation, from the oak tree.

The oxen of Oxford were celebrated last summer with the creation of 30 life-size ox sculptures, each painted by a different artist or company. Placed at different locations throughout the city in an ‘ox trail’, they were sold off to raise £150,000 for a local hospice charity.

Picture credits: Main picture: painting is Ox by Thomas Roebuck, about 1850. John Davies Fine Paintings/Bridgerman Images; Second unattributed, Bridgerman Images.