Float like a butterfly

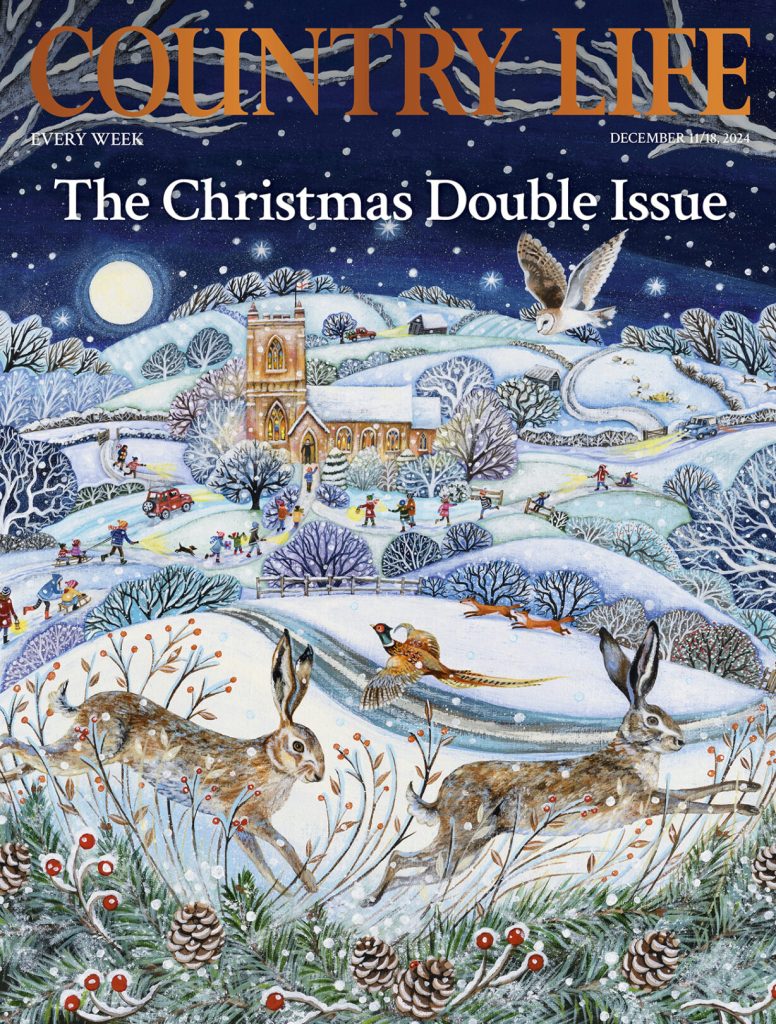

Finding nature in one of the most artificial artforms, classical ballet. This piece stemmed from a writing-class prompt to explore the representation of nature in an art form. It was published in the Christmas 2024 edition of Country Life magazine.

On the face of it, classical ballet has very little to do with Nature. As an art form that almost exclusively takes place indoors, it is a highly technical and entirely human activity, frequently set in the realm of fairytales.

Yet even make-believe worlds call upon the natural one. In creating The Royal Ballet’s festive production of Cinderella, designer Tom Pye says he was heavily influenced by Nature, flowers in particular. Both he and costume designer Alexandra Byrne were inspired by the depictions of fairytales by Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, both well-known early 20th century illustrators. Dulac also produced illustrations for Country Life.

‘They each draw upon Nature and play with scale, putting flowers at the forefront as framing tools,’ says Mr Pye.

His Cinderella set features tall, gilded meadow grasses at each side of the stage and the famous ball is now a garden party. The Royal Ballet is performing the choreography first devised by Sir Frederick Ashton in 1948, which features dances by four fairies representing the seasons of the year. Mr Pye’s designs incorporate very specific flowers for each: from spring bluebells and autumn leaves and berries to the Winter Fairy’s hellebores. Video technology amplifies the blooms into a riot of flowers in vaulted ceiling of Cinderella’s gradually-transforming house.

For English National Ballet’s brand-new production of Nutcracker, designer Dick Bird spent ‘a lot of time studying icicles’ in wintry landscapes as he created a spellbinding land of snow and ice.

‘We have icicles dripping from the twisted branches of snow-laden trees and shimmering on the headpiece of the ice queen, while the dancers’ tutus act as snow flurries.’

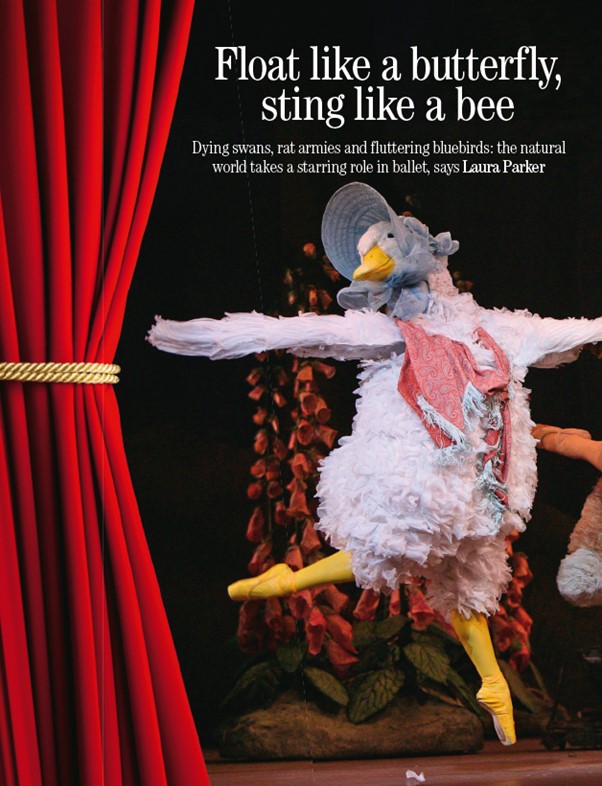

Over at Birmingham Royal Ballet, natural elements for its traditional Nutcracker include a magnificent 30-foot Christmas tree providing the backdrop for act one, at the end of which the young heroine Clara is carried away by a giant goose.

Animals and birds run, soar and glide their way through the classical ballet canon, from the dancing mice and fighting rats of The Nutcracker to the comic farmyard chickens in La Fille Mal Gardée. These roles are performed by dancers, although recent productions of Fille by both The Royal Ballet and BRB have featured a live pony – the diminutive Peregrine, a miniature grey Shetland who carries the heroine away in a little cart at the end of act one. His appearances always make the audiences gasp with delight.

Creating animal roles is a challenge for designers and dancers. The costume department must help the audience understand which animals or birds are represented while allowing full freedom of movement. Dancers have to perform while wearing wings, horns and antennae. Masks can inhibit vision and feathered swan headpieces, however beautiful, can muffle the music.

‘Tails can be tricky,’ admits Kit Holder, artistic co-ordinator at Birmingham Royal Ballet who has danced numerous animal parts including King Rat, who leads his rodent army against the Nutcracker and his toy soldiers.

Mr Holder’s favourite part of all time, and the one he chose as his retirement piece, is the Brazilian Woolly Monkey in Still Life at the Penguin Café, a ballet about animal extinction created by choreographer Sir David Bintley in 1988 and one which has only increased in resonance today. ‘The part involves a very demanding ten-minute non-stop solo, wearing a heavy head mask. It becomes a challenge of survival in itself!’

Another notoriously difficult role that mimics the movements of living creatures is the Bluebird pas de deux in Act Three of Sleeping Beauty. Two dancers, dressed in blue and adorned with feathers, spin and flutter, beating their legs together in the air in batterie and using soaring lifts as the male bluebird character, who stays aloft as much as humanly possible, teaches Princess Florine to fly. Based on a tale by Madame d’Aulnoy, a 17th century French fabulist, the bluebird is, of course, really a king who has been transformed into a bird.

Most classical ballets are based on folktales and many feature transformations – after all this makes for good visual drama in a wordless artistic medium. People turn into birds in many Norse and Germanic legends, and one that has most famously been translated to the ballet stage is Swan Lake. Here, a princess is transformed into a swan by an evil spell which can only be broken by the love of a young man. The large, enigmatic swan, serene and graceful, elegant yet fierce, lends itself supremely well to ballet. Swans can sail, glide and fly and they are vulnerable to hunters – the ‘swan’ Odette is nearly shot by Prince Siegfried.

Ashley Coupal, an artist of the company at English National Ballet, has played all of the swan roles in Swan Lake, including being part of a spectacular corps de ballet of 60 swans – double the usual number – at the Royal Albert Hall. ‘I really did feel part of a flock. It was very special because it shows how ballet can transform us.’

Rosanna Ely, a first artist at Birmingham Royal Ballet, says that although Swan Lake is the hardest of ballets to perform, the sensation of swans moving in unison creates ‘a unique feeling of powerfulness.’ She elaborates:

‘Just like a swan beneath the water, our feet are furiously working to move us across the space, while our upper bodies depict elegance and poise, and the port de bras movements of the arms mimic the expansive extension of a swan’s wings. This is the magic of the swans: they have both delicacy and pure power.’

One of Swan Lake’s most famous dances is that of the cygnets (petits cygnes) when four ballerinas, linked together, perform with absolute precision. It takes human coordination to an extreme, but again it is based on Nature. The choreographer Lev Ivanov, who created it for the 1895 Mariinsky Ballet production in St Petersburg, meant the dance to imitate the way cygnets cluster and move together for protection. ‘It’s the ultimate swan movement,’ says Ashley Coupal. ‘Only the heads move on top, while below the feet are very quick, very pointed.’

Several classical ballets including Coppélia are placed in a rural setting and feature seasonal celebrations as noblemen and peasant girls dance through bucolic scenes. Giselle opens with a wine harvest but soon moves to a deep, mysterious hunting forest haunted by vengeful spirits.

The rhythms of the seasons are woven into the fabric of many works, perhaps finding their pinnacle in Rite of Spring, a ballet that caused a sensation when first performed in Paris in 1913, with its atavistic ritual celebration of the advent of spring which results in a young girl being chosen as a sacrificial victim and dancing herself to death, all to Stravinsky’s urgent, pounding score. The modernist ballet, now widely accepted as part of the classical canon, shows more clearly how dance stems from something elemental. People have always danced: to express themselves, to give thanks to gods, to put on a display, and to perform to others.

Animals also make dance-like movements for courtship, defending territory and communication. We can think of the lekking black grouse, the strutting bird of paradise and the waggle-dancing bee. For humans, dance expresses the intangible in a physical form. The formal ballet art form is about interpretation, and animals and nature become our translators. The Dying Swan, famously performed by Anna Pavlova, see panel, is ‘not about a woman impersonating a bird’, according to dancer and author Allegra Kent, ‘It’s about the fragility of life – all life – and the passion with which we hold on to it.’

Perhaps, deep within us all, Nature needs us to dance.

Arguably the most famous prima ballerina of all, Anna Pavlova, had a signature dance which she performed 4,000 times all over the world in the early years of the 20th century. It was The Dying Swan, a four-minute solo piece choreographed by Michel Fokine and danced to the music of Le Cygne from Fauré’s Carnival of the Animals. A highly demanding piece, it is performed almost entirely en pointe. Anna Pavlova was an animal lover who kept birds, cats and dogs, and also choreographed her own Dragonfly dance. In 1912 she bought Ivy House on Hampstead Heath, stocking the ornamental lake with swans which she fed daily. She developed a particularly close bond with a swan that she named Jack and was photographed with him several times, his neck intertwined with hers.

On her deathbed in 1931, dying of pleurisy at the age of 50, Pavlova’s last words were ‘get my Swan costume ready.’

Several ballet techniques deliberately echo animal movements. Very young dancers learn how to hop like bunnies and develop flexible hips by doing ‘froggies’ on the floor. A basic move is the pas de chat (cat step) – a light jump from one foot to the other. Older girls yearn to do the dramatic, partnered, fish dive. Ballerinas aim to achieve bird-like elevation through soaring moves and effortless lifts. The most powerful ballet jump is a grand jeté with the legs extended, like a leaping cat. When a male dancer extends one leg in the air and beats the other against it this is a cabriole, derived from the word for a young goat.

In Sir Frederick Ashton’s The Dream, based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the male dancer playing the role of Bottom not only wears a donkey’s head in one scene, he has to perform a comic dance entirely en pointe – a technique that is usually the preserve of the ballerina.

images: Shutterstock, Getty, Alamy. Cover by Lucy Grossmith