Walking with the Colonel: the d’Arcy Dalton Way

The evening sun was yawing down the Ridgeway as we approached Wayland’s Smithy. It was the shortest day of the year and we’d walked 66 miles to be here.

We’d taken our time. Our journey to this neolithic long barrow at Oxfordshire’s south-western tip had begun on a grey January day eleven months previously. In a year of leisurely walking – fine weekends only – we had completed the d’Arcy Dalton Way, one of the Cotswolds’ lesser-known walks.

For years I had come across local green signs indicating this bafflingly-named route. That new year I resolved to find out where it actually went, and then to walk it. My newly-graduated daughter Kitty, stuck in that early living-at-home phase, was willing to come along, as was our chocolate lab Boswell, who accompanied us every paw-step of the way. It was going to be our walking project.

The route was created in 1986 to honour the splendid-sounding Colonel W.P. d’Arcy Dalton, founder of the Oxfordshire Fieldpaths Society. It skirts the county’s easterly borders, beginning in a low-key way at Wormleighton Reservoir, just over the Northamptonshire border where the HS2 line scars a shallow valley.

A small wooden sign points to a narrow footbridge, where we took a quick selfie, to the indifference of the swans sailing on the water. Then we were off, managing only a couple of miles before having to retrace our footsteps to the car. From then on it was a two-car shuttle: parking one vehicle at the end of each leg.

The d’Arcy Dalton passes pleasantly through the polite heart of middle England, from the rolling Cotswolds to the Thames Valley. Stately homes bracketed the walk and marked the seasons for us: Farnborough Hall’s parkland was dotted with daffodils and young lambs on a brisk February day. By the time we reached the exquisite French-style mini chateau of Cornwell Manor near the halfway point, marquees from summer weddings were wilting in the heat. Autumn took us past the great wall at Barrington Park, while in December we were greeted by the sight of Buscot Park’s ice-covered lake fringed with frosty branches.

Although the walk offers neither high peaks nor dramatic coastlines, it does have variety. Some twelve miles in, there are enjoyable small hills to skirt in the ‘Redlands’; the ironstone country to the north of Banbury, where the houses are built in Hornton stone’s distinctive brown sugar fudge. Hook Norton with its perpendicular church tower and famous brewery is the last of these villages. From then on, the stonework gradually mellows to a more delicate pale honey as it nears Burford. After that, it is largely level walking across meadows on the approach to the Thames. By this stage, the Wessex Downs are underlining the horizon. The sight of the Uffington White Horse etched on their slopes motivated us on our last and longest day, an eleven-mile leg from Coleshill village.

We crossed rivers, streams, railways and a motorway. We didn’t always – in fact sadly hardly ever – end up at a pub, but can give honourable, thirst-quenched mentions to the Bell at Shenington, the Chequers at Churchill and Ye Olde Swan at Radcot.

We passed through churchyards and backyards: the footpath sometimes heading straight across lawns and orchards. I won’t forget the fourteenth century ‘doom’ – a painting of the Last Judgement – the faces of people being dragged to hell still vivid on the wall of the church of St John the Baptist in Hornton.

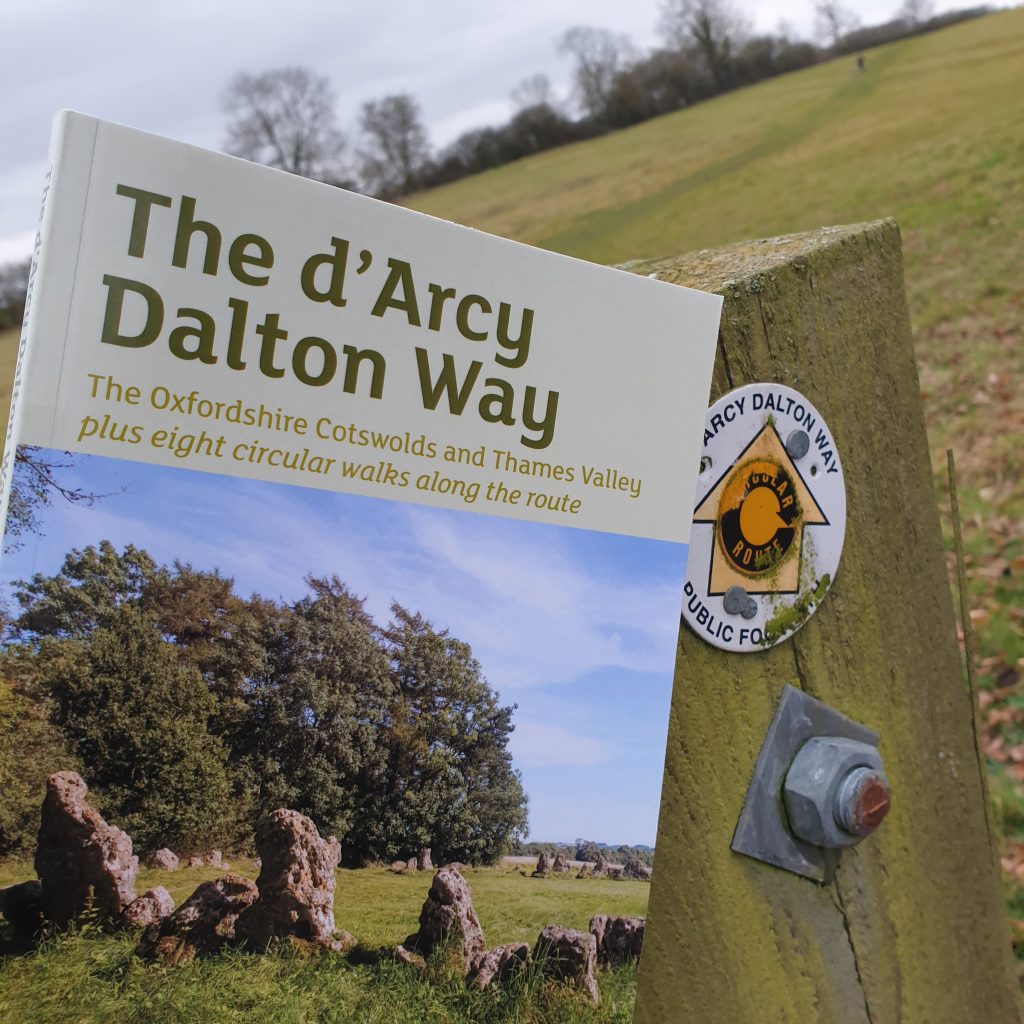

The church visit was prompted by our invisible but very capable guide, Nick Moon. His book on the d’Arcy Dalton Way, last updated in 2021, is extremely detailed, largely accurate, and essential. We soon learned that the signposts that had prompted me finally to tackle this walk are not always as prominent, or even there. It also contains neat and easily digestible mouthfuls of history about the places of interest.

In his hands we discovered sunken ways, ghost villages such as Tangley abandoned during the Black Death, and learned that Taynton stone, dug from a quarry near Burford, provided the building materials for St Paul’s Cathedral and many Oxford colleges. We found out that the brass figure on the war memorial at Westwell had been stolen from the Cloth Hall in Ypres, and that the council houses in Filkins were built on the orders of Sir Stafford Cripps, the post-war Labour Chancellor, who in 1928 wanted to demonstrate that social housing could be made to blend in with traditional village dwellings. At Longcot, we knew to seek out the gravestone of Lilian Carter who gave up the last place on the last lifeboat to stay with her husband on the Titanic. By the time we approached Radcot near Lechlade, we were immersed in tales of the strategic battles fought over its bridge in both 1387 and during the English Civil War.

The guidebook’s directions occasionally involved trees, instructing us to head towards a group of beeches, a willow by a fence, or a lone ash. This is fine if you know your trees, but also a potential problem: trees get chopped down or succumb to die-back.

Along the way, we met very few people, mainly dog-walkers within close range of the villages. Only two couples stopped for a chat, both on the same day. One pair wanted to find the nearest pub and the other two were seeking out the summer fete at Kingham. By coincidence, all were holidaymakers from Preston. For the rest of the time, we hardly saw a soul.

There were almost as few encounters with animals: this once wool-rich country is now almost devoid of livestock, but we needed to be alert for cows with calves in spring and summer. Near Alkerton, we had to find a diversion round a lively group of curious Guernseys, and at Sibford Ferris we ran the gamut of a gauche gang of bullocks clustered round the exit stile.

What else did we learn about the countryside? That arable land is hard going in the winter, especially if the footpath has yet to be marked on a recently ploughed field. That some farmers don’t welcome the route, but that when they remove signs it only makes hikers more, not less, likely to stumble where they’re not wanted.

We walked companionably, and we talked. My daughter mused on her career struggles, break-ups, fruitless Hinge dates, and being stuck with her parents. We discussed health; her tiredness, moodiness, and altered appetite. By the end of the year, blood tests showed she had hyperthyroidism: suddenly it explained a lot. Boswell, meanwhile, never flagged and only complained if he was not allowed to sit under our pub table.

On that last evening, all three sharing ham sandwiches as the sun flamed the beech trees around Wayland’s Smithy, we experienced a very satisfactory feeling of completeness.

A twelve-month walk is a good way to pace out a year.

Gen Sandalls

Really enjoyed your piece. It was beautifully written and evocative of a landscape largely familiar to me.

Laura Parker

Thank you!

Lisa Turner

We are currently walking the route having spotted signs over the years and finding a guide book in a charity shop – have you seen the YouTube blog by ‘Wiltshire Man’? Worth a look. My copy of the guidebook is from 1999 so no wonder we are struggling with a few of the directions. Lovely walk though.

Laura Parker

Great to hear you are enjoying the walk and thanks for the YouTube tip. Agree that it can be hard to find the signs and directions at some points. Nick Moon was fond of using trees for directions and some of those, eg ash trees, aren’t there any more. Also some of the footpath signs have been allowed to disappear, especially around farms. Quite a common occurrence! Good luck with the rest of the walk!

John

Thanks for your great summary.

I bought the guidebook some 20 years ago, but now decided to give it ago. Set off in reverse from Wayland Smithy after an horrendous storm in January. First stretch to Longcot was horrendous. Wading through deep mud and flooded fields. Wish I had wellies. Lol. Hopefully the land will dry out as I hit the Cotswolds in the next couple of stretches. Never saw a sole.

Laura Parker

I recall that muddy flooded stretch! It was the worst and wettest part of the walk, so things will get better, esp after you reach Burford. Good luck and hope you enjoy the trail.