Broadway twilight

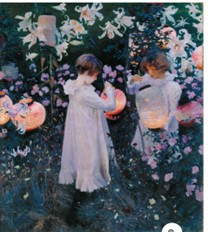

The man takes a step back, and looks again at the girls amid the flowers. His round felted hat is dipping over one eye. The two paintbrushes, woven between left fist and palette, seem to hesitate. Dolly takes a glance to her right to see if it is safe to move yet. The lily flower’s head, directly behind her sister, is beginning to droop, the light held in its golden stamens fading in the August evening. It must be nearly time to stop. Polly, opposite, is getting restless too. Their eyes meet, saying, silently, lemonade. Polly’s mouth twitches.

Last summer it was fun. Dolly remembers the excitement of having their smock-like white dresses made. Now they are nearly twelve and eight, and her dress is tighter round the arms, while Polly’s is shorter. Mr Sargent says the roses in front of her will hide the hem. They still love to light the magical lanterns, when they are allowed to do so. Tonight they have been asked simply to stand, and to look down.

“Just time for a couple of games before we lose the light, John!” comes the welcoming roar of their father, approaching, tennis racquet in hand.

The artist straightens up, and turns. “Very well, Frederick. The light here has passed for this evening, although I did catch some of that extraordinary mauve for a few seconds.” He turns to the girls. “Thank you, young ladies, you are released.” The girls move with relief as he continues: “You’ll put everything away, won’t you now.” It has become the routine. The men walk, talking, towards the tennis court on the lawn at the other end of the garden. The girls begin each to collect three lanterns and take them carefully into the barn. They will come back for the paintstuffs after they have changed out of their dresses. Then they will be free to go back to their friends.

This summer the artists’ colony has grown and there are now fourteen children of various ages living among three residences around the village. Two recently-arrived families are staying in the Lygon Arms, Broadway’s great coaching inn, and Polly has found a gaggle of other small girls who assemble on the village green daily to roam and play by the small stream. Little dark-haired Katharine Millet, though two years younger, often takes the lead.

Dolly glances at the large canvas as she passes. Perhaps a few more roses have been added this evening, she is not sure if she can tell. She knows that tomorrow he could easily have scraped them off again. Will he ever finish, she wonders. Last year he worked on into the autumn, allowing them to wear long white sweaters under their dresses as the evenings grew chillier while he draped himself in a dark woollen cloak, one end flung dramatically over his left shoulder.

The painting has become the talking point of the artists’ community. Even though the other painters are engaged in their own endeavours, some producing landscapes, some working painstakingly on interiors, others chiefly enjoying lounging, talking and games-playing – and even though the artist is working on other portraits – this work is the centrepiece. They often gather at the end of the day to admire the canvas against the studio wall once he has taken it inside, carefully, and with some difficulty. It is taller than Dolly and wider than she is high. His new plein air technique fascinates some, is dismissed by others. “It’s all very well in France,” she heard her father snort. “But look at that English rain coming in again, eh?”

Dolly suspects the artist is in love with this method of painting. Last summer, at the other house, he would catch them playing and ask them to stop like statues, while he ran to get his sketching materials. Some of the other guests make gentle fun of him. Dolly overheard Mr Edmund Gosse compare his idiosyncratic methods to the actions of a little wagtail: “He waits for a certain notation of the light and runs forward over the lawn, planting rapid dabs of paint, retiring again, only to repeat it.” He is bird-like, although when he had his winter cloak on he more resembled a large black crow.

Dolly sets off towards the kitchen, where the jug of lemonade will be standing on a cool stone shelf.

Here comes Lily Millet, striding through the dusk, a dainty copper mister in hand. She stops to examine the standard rose, resolves to come back with secateurs the next day. Checks the lilies, puts their spectacular faces nearly in hers. Such pride to see them flourish in their pots, staked high. Lilium auratum. One of her greater gardening achievements. When Sargent bought her the 50 bulbs in spring, asking her to grow them in readiness for this second summer of the endless painting, she quailed a little, but he insisted. This work had become a typically flamboyant endeavour. Frank’s interiors proceed quietly, but Sargent rushes at things differently. Last summer when he arrived to recuperate from a head injury he had acquired by diving into the Thames – and to recover from that debacle in Paris over that risqué painting of Virginie Gautreau1 – he talked frequently of Chinese lanterns by the river in Pangbourne, a scene that had made a tremendous impression on him. Coming to this Cotswold backwater was a release, he said, a chance to work on a major canvas en plein air, free to capture richness, saturated light, new colours. And the lilies. New, costly, paradisical. Lily suddenly notices the single L. speciosum rubrum, with its red-spotted flowers and delicate pink flush, is dropping further. She resolves to tie it in tomorrow.

She walks round to look at the canvas. In the soft dusk, its lanterns and lilies glow, while the roses and carnations are more dimly presented.

Then Sargent is at her shoulder, Frank too, panting from the tennis. They are ready to lift the painting into the safety of the barn. “It’s too damn’d big, John,” complains Frank as he moves to take one side. “Do you know, I think you may be right,” says John, taking the other.

Lily waits until the barn door closes and then the three of them turn towards Russell House, where the light is spilling out of the open door. Singing can be heard, with laughter and clapping. Soon the dancing will begin again.

Dolly looks out of her bedroom window as the moon lifts above the elm trees, casting fading shadows over the lawn as the flowers dim from view.

© Laura Parker 2023

1 The painting known as Madame X