The cypress trees of Provence, and, eventually, van Gogh

“…two studies of cypresses of that difficult shade of bottle green”

Come September, my yearning for a Keatsian beaker full of the warm south was growing stronger, and the prospect was getting closer. I had set out the criteria earlier in the year. Holiday must contain: a blue Provencal evening. Stillness. A stone terrace. Bougainvillaea. Scent of the macchia rising slowly. If no nightingale in full-throated ease, then at least a cicada thrum. Most important, a view. Pantiles on a distant perching village. Soft greys and mauves of olive groves and citrus orchards. All punctuated by the exclamation marks of the narrow cypress trees: firm dark pen lines against pencil and wash.

Those cypresses felt particularly important. I knew I had arrived as soon as I saw those dense upright tails, their points swirled like the tip of a painter’s fine brush.

The mediterranean or Italian cypress, aka Cupressus sempervirens, is the slender key to the landscape of south-eastern France and northern Italy. They are as regionally symbolic as a Scots pine by a loch or an oak planted deep in English parkland. The stylised travel posters of the early twentieth century abound with them: bright lines of lavender converging on cones of green, solemn spikes amid precipitous shorelines running down to a white-waved azure sea. The trees have featured in the stories, poems and paintings of the Provencal landscape for many generations.

Cupressus sempervirens, the name meaning always flourishing or growing, are long-lived. Some have survived for over a thousand years. Like our British yew, they are widely seen in cemeteries as a symbol of longevity. Another more practical reason is that their roots grow straight down and only slightly laterally, so they don’t disturb the gravestones. Standing sentinel in a graveyard, they have also come to represent death and mourning.

There is of course a classical myth attached to such ancient trees. Cyparissus, a young man loved by Apollo, had a beloved pet stag which he killed by mistake while out hunting. His grief and remorse were so inconsolable that he asked to weep forever, so Apollo duly transformed him into Cupressus sempervirens. His tears are the tree’s sap.

Scattered among the Provencal landscape, cypress trees acquired their own legends, for example as a hidden hospitality code for travellers. Three planted at the entrance to a mas – a country farmhouse – meant visitors welcome. One tree? Best stay away. This early TripAdvisor rating was not always understood by Parisians rushing to buy a second home in the property boom of the 1980s, who would see the trees and think of their sombre city cemeteries. Provencal estate agents rapidly revised this view, assuring their clients that cypresses brought a household good luck.

Aside from its mythology, cypress has many uses. It’s a strong building material, and its durability has made it the choice for the doors of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, as well as farms and barns. The beam in our accommodation bedroom looked like a cypress trunk that had been hewn, stripped, and heaved there probably two hundred years previously. Cypress has traditionally been used to make coffins (including that of Tutankhamun) as well as furniture, and Italian harpsichords. It has lent its aromatic and astringent properties to fragrances and cosmetics for firming skin to preventing dandruff.

They have also figured frequently in art, showing up in a huge range of works from fifth-century friezes in Persepolis to the civilised Tuscan backgrounds of Leonardo da Vinci’s 1472 Annunciation. They also honourable mentions throughout literature, from the fourteenth century Persian poet Hafez to Shakespeare, making cypress variously a metaphor for faithfulness, commitment, and mourning.

In 1874, Jean Aicard, a French poet who is as much associated with the Midi as Wordsworth is with the Lake District, produced a volume titled Les Poèmes de Provence. The poems’ subjects include wheat, figs, cicadas, hives, reeds – and cypress trees. Les cyprès celebrates the particular appeal of the southern cypresses and how they differ from their funereal northern counterparts, appearing much greener against the pure blue horizons. (« plus verts dans le bleu pur des cieux »). In the poem, cypresses stand as grenadiers on a dusty track and surround gardens full of playful children. Their laughing shade (ombrage riant) provides a home to the finch and the cicada, and shade for lovers’ kisses. Rather beautifully, their undulating tops test the wind’s strength. (« Par leur faîte onduleux jugeait l’effort du vent. »)

Fourteen years after this poem was published, a Dutch artist arrived in Provence, attracted to the region for its unique light. Vincent van Gogh painted his first cypresses in the town of Arles, where he lived from February 1888 until he entered the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence the following spring with a diagnosis of epilepsy. His year there was both turbulent and productive. He completed over 150 paintings in his studio overlooking the gardens and painted outdoors in the surrounding landscape. Many canvases were filled with the pines, olive groves and wheatfields that he saw. Cypresses, painted forcefully and emphatically, began to feature prominently.

Trees held an emotional and spiritual resonance for van Gogh: “In all of nature, in trees, for instance, I see expression and a soul.” In his first year in Provence he painted orchards and olive trees. Cypresses, at first a backdrop to these other trees, for example in Orchard with Peach Trees and Cypresses (April 1888), began to move into the foreground during his asylum year.

In the ‘fine, hot days’ of June 1889 at St Rémy, he began a series featuring cypress trees, writing to his brother Theo: “The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it astonishes me that no one has yet done them as I see them.” He mentions having made “two studies of cypresses of that difficult shade of bottle green.”

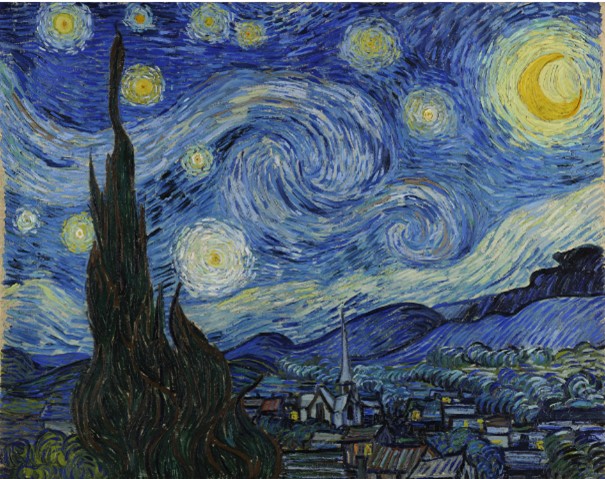

He had recently completed Night Effect, now known as The Starry Night and regarded as one of the three most famous paintings in the world. The roiling, boiling, swirling sky of tumbling blues and yellows, which takes up the top three-quarters of the painting, is its chief mesmerising attraction. But on the left hand side, reaching up through the yellow fireballs, lick the dark flames of a cypress tree. Its deep colours absorb the glow of the stars, although sparks of yellow appear within its charcoals, browns and greens. The tree contains nearly all of the painting’s upward brushstrokes. Van Gogh had written in the previous year how he wondered if “we take death to reach a star” in the same way as catching a train to a destination. Does the presence of the cypress, as some commentators including contemporaneous art critic Gabriel-Albert Aurier and psychoanalyst Albert J Lubin have said, represent a sombre route to the bright heavens above? Or did cypress trees exert their own fascination and painterly challenge, as we see in that same letter to Theo:

[the cypress tree is] beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk. And the green has such a distinguished quality. It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape, but it’s one of the most interesting dark notes, the most difficult to hit off exactly that I can imagine. Now they must be seen here against the blue, in the blue, rather.

The two trees in Cypresses, painted next in the series after The Starry Night, do not have the static, regular proportions of those obelisks. Now the main subject, the trees are full of movement and life, reverberating with softer, fuller curves in a brighter green as they reach up through a daytime sky – one where the crescent moon is still visible – right out of the picture. This time their tops are unseen. The trees tower over the distant, violet mountains. Their trunks are licked by profuse summer undergrowth, “thickly impasted tufts of bramble with yellow, violet, green highlights,” in van Gogh’s own description.

Other works in the cypress series include the bright, airy Wheatfield with Cypresses, painted en plein air in the summer of 1889, and Road with Cypress and Star, also known as Country Road in Provence by Night, a studio composition painted just before he left the asylum in May 1890. This painting puts a sole large cypress, now in more muted blues, at its very centre, with a sun and a moon on either side. It was to be van Gogh’s last painting in Provence.

Shortly afterwards, the artist returned to the north. Discharged from the asylum, he moved to Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, to be closer to his brother and to receive treatment from Dr Gachet, a specialist in melancholia with an artistic circle of friends. Vincent van Gogh continued to paint landscapes until he took his own life on 29 July. He was buried the following day. An obituary noted that his coffin disappeared under bouquets of sunflowers and branches of cypress.

None of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings are now in Provence, but the cypress sempervirens remains, continuing to exert its everlasting fascination – to me, sitting on my stone terrace, at least.